Jenkins Pipeline has rapidly become one of my favorite tools in the entire Jenkins ecosystem. Part of my job at CloudBees has been advocating for its use, but I can confidently state that I would be a passionate user of Jenkins Pipeline regardless of who was paying me; it is simply better than what preceded it. As Pipeline has evolved and matured, I have pushed for its unilateral adoption within the Jenkins project’s own Jenkins environment. Wielding Pipeline as a developer is one thing, managing infrastructure which utilizes it is quite another.

As a Jenkins administrator, my two main concerns are: effective resource

utilization, and reducing my support burden. Using Jenkins Pipeline means that

developers can commit a Jenkinsfile to their repository and

“choose-their-own-adventure” with their continuous integration and delivery

workload. I can, and typically do, go one step further by enabling a GitHub

Organization Folder which automatically adds repositories and branches which

contain a Jenkinsfile, allowing new repos to be created and automatically

incorporated into the Jenkins environment. This flexibility comes at a cost,

consider the following contrived Jenkinsfile:

node('some-very-expensive-instance') {

sh 'while true; do echo "Lol"; done'

}

Perfectly valid, but as an administrator, completely annoying. The above example will allocate resources in the Jenkins environment, and then run an infinite loop, tying up those resources until somebody notices. While I hope none of the developers I work with would be so intentionally abusive to the Jenkins infrastructure, it’s easy to guess how different usage patterns might cause an infinite loop (check an external resource before proceeded, except the external resource never gives the response desired), or more likely, an exceptionally long Pipeline run caused by wedged tests. If only I had a mechanism for automatically applying a timeout to operations!

Consider a different scenario. To provide better console output, shell scripts should have a timestamp in the log and should use colorized console output for better readability. Perfectly doable in Pipeline:

node {

ansiColor('xterm') {

timestamps {

sh 'make check'

}

}

}

Unfortunately, I have no way to mandate that every Jenkins Pipeline uses this exact same pattern. Expecting every developer to follow this pattern is terribly unlikely.

Fortunately, Pipeline gives me a mechanism to solve both problems here:

Shared Libraries. To

address the latter example, I could created a Shared Library, which provides a

global

variable

goodsh, defined in a file named vars/goodsh.groovy, which encapsulates the

use of ansiColor and timestamps. A Jenkinsfile utilizing this Shared

Library could be made much more concise:

node {

goodsh 'make check'

}

Much better! Except now I am relying on everybody knowing about my goodsh

global variable, and using it in their Pipelines.

Overriding built-in steps

Fortunately this can be accomplished by overriding built-in steps with the Shared Library. I consider this a feature of Shared Libraries, but there’s no telling who might consider it a bug instead, so your mileage may vary!

Reconsider my goodsh global variable above, what if I rename that file to

vars/sh.groovy, then I could invoke the global variable sh right?

Bzzzt! Stack overflow. Lucky for me, there is a hidden variable in the

scope called steps, upon which the built-in steps have been made available.

If I change vars/sh.groovy to the following, everything works nicely:

def call(Map params = [:]) {

String script = params.script

Boolean returnStatus = params.get('returnStatus', false)

Boolean returnStdout = params.get('returnStdout', false)

String encoding = params.get('encoding', null)

timeout(time: 2, unit: HOURS) {

ansiColor('xterm') {

timestamps {

/* invoke the built-in sh step */

return steps.sh(script: script,

returnStatus: returnStatus,

returnStdout: returnStdout,

encoding: encoding)

}

}

}

}

/* Convenience overload */

def call(String script) {

return call(script: script)

}

In the global variable implementation above, I can define some really useful

defaults for sh invocations in the Jenkins environment. First, and probably

most importantly, I can apply a global 2 hour timeout for any single sh

invocation. And second, I can apply some nice, prettifying defaults, courtesy of

the ANSI Color plugin and the

Timestamper plugin.

How it works

When I showed my pal Andrew, one of the primary developers of Declarative Pipeline syntax, this “feature,” he was surprised to say the least. It just feels weird doesn’t it? The reason this works all comes down to goofy tricks with scope in Pipeline, a Groovy-based domain-specific language. To demonstrate, let’s do something foolish:

node {

/* assign a variable */

def sh = 'lolwut?'

sh 'printenv'

}

Predictably, this will raise an exception at runtime:

groovy.lang.MissingMethodException: No signature of method: java.lang.String.call() is applicable for argument types: (java.lang.String) values: [printenv]

The Pipeline is adding a sh variable to the current scope, which is being

resolved first when we attempt to invoke sh 'printenv' on the next line. Of

course, a String variable is not callable, an exception is thrown.

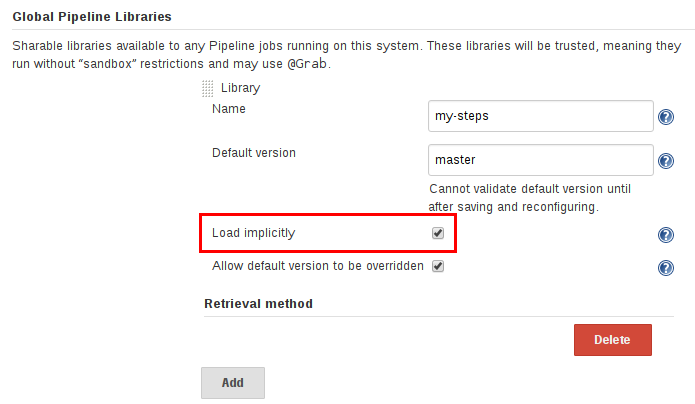

It is this principle that overriding steps is based upon. Since Shared Libraries allow me to inject my own global variables, I can create a Shared Library which overrides key built-in steps. In order to make my overrides default however, I must add a “Global Shared Library” inside the “Configure System” page:

Since this is an administrative option, I have the power to make these overridden steps required for all Pipelines executing in this environment.

Overriding steps is obviously an advanced use-case, and presents some risks. For example, you should never load a Pipeline Library from an untrusted source. Not only because steps can be overridden, but also because Shared Libraries are considered “trusted” in the Pipeline runtime. Additionally, if you decide to override built-in steps, always preserve the same call signature as the built-in step, otherwise users will quickly find that what they’re invoking isn’t what they expect, and will probably get upset.

This approach, implemented properly, can be quite beneficial as users get additional functionality “for free” from their existing Jenkins Pipelines!

If you’re interested in talking about more crazy Pipeline hacks, I invite you to join me at Jenkins World 2017 in San Francisco, August 28th - 31st.