The Delta Kernel is one of the most technically challenging and ambitious open source projects I have worked on. Kernel is fundamentally about unifying all of our needs and wants from a Delta Lake implementation into a single cohesive yet-pluggable API surface. Towards the end of 2025 TD asked me to jot down some of the issues which have been frustrating me and/or slowing down the adoption of kernel in projects like delta-rs. At the outset of the project we all discussed concerns about what could actually be possible as we set out into uncharted territory. In many ways we have succeeded, in others we have failed.

Reviewing the history, I was the second developer to commit code behind Zach to the project. Like all open source projects, Delta Kernel is the work of numerous people who have all poured their time into making something happen together. I regularly work with Robert, Zach, Nick, Ryan, and Steve to make delta-rs and delta-kernel-rs better.

While we all have our personal motivations, we also have direction guided by our employers in some cases. That means the goals for kernel from Databricks may not align with my employer (Scribd), or others participating in the project. This complicates trade-off decisions in many open source projects where personal, professional, and hobby motivations intersect.

My hope is to characterize the weaknesses in kernel so that we can collectively adjust in 2026 to make improvements in both the technical design of kernel, but also the community and culture around kernel.

Design

From my perspective the original design trade-offs made in kernel were largely driven by two key factors:

- Portability with non-Rust engines: this dictated the need for an FFI abstraction on day zero. The Delta extension for DuckDB had an outsized influence on this due ostensibly to a desire from Databricks to make DuckDB and Delta be best friendsies.

- The Java kernel: the Delta kernel is actually two implementations, one in Java for unifying JVM-based connectors, and one in Rust for basically everybody else. Due to the number of folks involved in the Java kernel, the Rust implementation was strongly encouraged to take design cues from the Java design.

More than anything these two factors have contributed to a number of what I would consider original load-bearing sins of design for delta-kernel-rs.

These trade-offs resulted in a Rust-based project which abandons most of the important benefits for using Rust.

Building for the lowest common Denominator

Supporting cross-language and runtime interoperability is brutal. I have done a lot of cross-language support for Ruby and Python projects in the past, where at some point somewhere there’s a pointer being passed from one world into another. It is objectively awful.

Over the years of delta-rs people have tried adding FFI hooks into it, despite us never making any accommodations for it. Seriously, as recently as this month somebody popped up with yet-another set of Golang FFI bindings on top of delta-rs.

FFI is hell.

A hell that we intentionally marched into with Delta kernel. For the uninitiated, FFI basically a convention for allowing multiple languages to meet at a C ABI layer and pass pointers back and forth. There is some more about memory layout and other silliness, but basically, it’s a way for everybody to dumb themselves down to a C-style interface.

FFI is also stupid but it is basically how all higher level languages work such as Python, Ruby, JavaScript, Golang, Rust, etc. Somewhere down there in the stack is a pointer passing into C-based system calls on your machine. There be monsters.

One of our early design disagreements made to accommodate FFI-based engines was

the adoption of Iterator based interfaces rather than Future based

interfaces. Previously I wrote about our parallelism

challenges which stem from this design

trade-off.

The debate was whether to hide an evented reactor like Tokio inside kernel and hide that from the FFI caller, or make the caller responsible for trying to make things event-driven. The early influence of DuckDB weighed on the scales here, and the decision was made to avoid embedding Tokio inside kernel.

In the Rust ecosystem it has taken a long time for us to become async. If you were curious why there has been such an explosion of Rust across the systems programming ecosystem in the last five years it’s because the Rust ecosystem is async.

The first Rust application I deployed into production used async/await from

the beginning, and without any profiling was an order of magnitude faster

than the system it replaced.

async/await is the reason delta-rs was even successful in the first place!

There are ways to hack around the limitations of the Iterator

based API in Delta kernel, but the hill is very steep and will require

significant investment to make some parts of Delta kernel as fast as parallel

reads/scans would otherwise be.

async/await gives incredible performance for free, but Delta kernel’s design choices mean it cannot take advantage and must pay the price.

EngineData

I am not smart enough to work on some parts of Delta kernel because of the

cleverness that is EngineData. Similar to

arrow-rs and its RecordBatch and

ArrayData implementations, EngineData is an opaque type-erased container

for stuff and things.

One of the reasons I struggled to learn to Rust, but ultimately came to love the language is the strong type system which helps prevent whole classes of problems. The strong type system also makes it a lot simpler for me to reason about the code when I am working with it.

Everything in Delta kernel is

EngineData

in one form or another. I was pretty preoccupied when this interface was

originally being hammered out so I’m less familiar with the history of

decisions that went into it, but I find the API of EngineData and its

counterparts of

RowVisitor,

GetData,

and

TypedGetData

to be very unpleasant to work with.

I also find

RecordBatch

unpleasant to work with. I really struggle to think of more user-unfriendly

APIs in the Rust data ecosystem. In the case of arrow’s RecordBatch I have

watched some of my colleagues pull in the entire

datafusion dependency just so they can

work with RecordBatch without resulting to the array offset and indices

silliness that permeates Apache Arrow code.

As unpleasant as I find RecordBatch there are thousands of developers

invested in its APIs and supporting infrastructure. EngineData does not have

a similar level of tooling, but shares some of the same razor-sharp edges.

The EngineData design has resulted in a lot of brittle fixed array

offsets

being littered throughout the Delta kernel codebase. These “getters” and the

visitors APIs result in the Rust type checker being far less useful with

Delta kernel than a more conventionally structured Rust project. This also

results in a much larger likelihood of runtime errors being emitted for

problems rather than compile-time checks.

The type-erased opaque bucket of bytes design of EngineData means that

working inside of or with Delta kernel sacrifices one of the most important

characteristics of the Rust language: the type checker.

There are some good pieces of the design which honestly I cannot speak to because I don’t stub my toes on them. Ryan and I have discussed at length the importance of deferring work as long as possible in kernel to achieve higher performance. Some of the Expression and Transform APIs allow for lower memory footprints and faster log replay when work can be deferred or outright avoided.

In delta-rs some of the performance deficiencies we have seen since adopting Delta kernel have more to do with our interop code rather than kernel design decisions. The delta-rs project is massive. As a general purpose Delta Lake implementation, the surface area of changes that Robert had to touch to even get to where we are today has been nothing short of heroic.

Community

The Delta kernel project is the first one I have worked on with Databricks where there is some transparency around the week-to-week operations. The kernel Rust community has weekly meetings where developers are talking to developers. Many of my early conversations with Denny were around the propensity for Databricks to dump code into the Delta project as a fait accompli. In one particularly egregious situation, there were protocol and Delta/Spark changes which were reviewed, approved, and merged by Databricks employees the week before being announced at Data and AI Summit. Kernel gets this right.

Even though I cannot make every weekly call with the kernel community, I love it when I can.

I don’t always attend the kernel weekly call, but when I do, I’m asking when the next release will happen.

For reasons I don’t think anybody really understands, Delta kernel moves very slowly. Patch releases are of particular importance to me because delta-rs has started to depend on the Delta kernel for its protocol implementation and therefore many of our new bugs relate to Delta kernel in some way or another.

Releases have averaged around one every three weeks in 2025. Nine of the thirty versions released to crates.io were patch fixes, which means 70% of published releases contained API breaking changes. Some of that is inevitable as developers are figuring out the appropriate shape of different APIs. As a consumer of this release cycle downstream this means that I am highly unlikely to ever receive bug fixes without requiring development effort to adapt to ever-changing APIs.

There is no free lunch.

For the delta-rs project this means our releases are frequently blocked on:

- Delta kernel

- Apache Arrow

- Apache Datafusion

Delta kernel ships with a default engine that has a major version dependency on

Apache Arrow, a project which also avoids patch releases. This compounding

effect means that when a new arrow is released we (delta-rs) must wait for

that to be incorporated into both datafusion and delta_kernel, and for both

those crates to be released.

Any issue reported to delta-rs which requires a change in Arrow or Delta kernel will typically take 1-2 months to resolve.

No need to wait

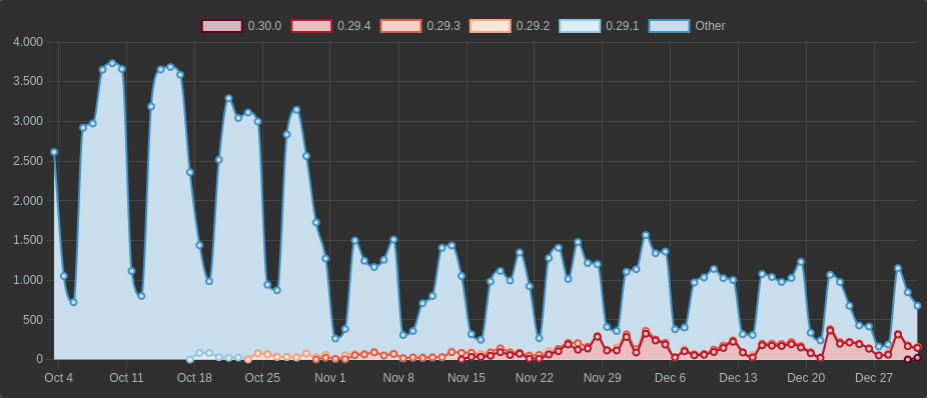

Up until yesterday, the latest released

deltalake crate was 0.29.4 which

depended on Delta kernel 0.16.0. That version is three months old and

unfortunately never saw any patch releases, which is part of the reason all four of the 0.29.x releases of delta-rs depended upon it.

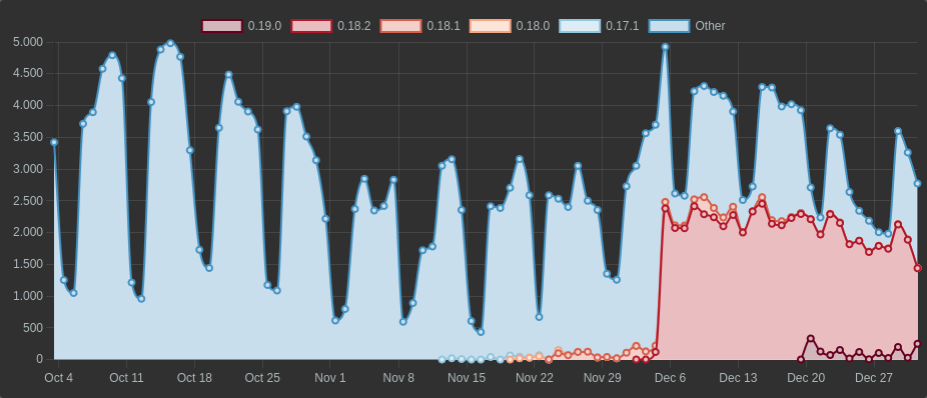

Using the crate downloads statistics as a very unscientific measure, I would

hazard a guess that delta-rs drives the majority of downloads for Delta

kernel.

The 0.18.0 release went out on November 20th, which has a small uptick, but

then the big spike in early December correlates strongly with the incorporation

of this pull request pulled

0.18.x into the delta-rs repository.

For completeness’ sake, the deltalake crate’s downloads have a very similar

shape. But due to the longer release cycle of 0.29.x is is difficult to tell

what versions are being heavily downloaded.

Maintaining stable APIs is a pain, but becomes much more important the lower in the stack any dependency lives.

One approach could be to create release branches which have changes cherry-picked between them as is needed. This introduces more release engineering work and can be challenging. For my own purposes I have done this and backported fixes for both Delta kernel and delta-rs in various shapes to support customers who cannot boil the ocean with unstable releases every two to three weeks.

At Scribd a patch release of delta-rs, with zero API changes requires at least:

- New Lambdas to be built.

- Those Lambdas to be deployed to a testing environment.

- waiting for enough data volume to demonstrate reliability

- Promotion of a Lambda to a production environment.

- waiting for enough data volume to demonstrate success

When everything operates smoothly this is about two developer-hours of time from end to end, but that is with zero API changes.

Every set of API changes in delta-rs, Delta kernel, or Apache Arrow introduces unknown developer time to perform updates and upgrades. Unless a new release of any of these dependencies confers significant performance or quality improvements, the business looks at these upgrades as unnecessary cost and instead prefers to simply not update.

As a consequence bugs can be discovered in production months after a given Delta kernel release. For example this performance bug in Delta kernel had actually existed for months in released crates. It was not until delta-rs adopted more of Delta kernel. Only then was I able to bring upgrades all the way to production and discovered a couple serious performance issues in delta-rs and Delta kernel.

This timeline is getting a little confusing even for me, so let’s recap:

- October 2024: A JSON parsing workaround introduced into kernel and released in

0.4.0. - July 2025: deltalake 0.27.0

released with first serious adoption of Delta kernel at

0.13.0. - August 2025: delta-rs performance issue identified and fixed along with a separate Delta kernel performance issue with wide tables identified. Both problems were identified after I invested some spare work-cycles in using pre-release code to interact with production data sets at Scribd.

- September 2025: oxbow incorporates 0.28.0 and that’s quickly reverted until delta-rs

0.29.xis released with additional improvements both in the crate an incorporated in the newer Delta kernel0.16.0.

From my perspective, the amount of time invested in the performance issues alone has not been “paid back” by improvements delivered from Delta kernel.

NOTE: HR would like to remind me to adopt a growth-mindset.

The improvements from incorporating Delta kernel have not paid back the time-invested yet.

For more than a year there were performance issues sitting in main and

released kernel crates.

The time delay between changes being made in kernel and those changes being used for real workloads is long. Too long to be useful as a constructive feedback cycle for development.

I believe the only way to improve this is with faster releases and faster feedback.

Have you tried just

The very-long user-feedback loops on released changes is only half of the velocity troubles afflicting Delta kernel. I have personally avoided contributing too much because the amount of yak-shaving can be pretty wild.

The performance improvement I recently suggested was a new personal TOP SCORE! Garnering a total of 84 comments in the back-and-forth with four different maintainers. That is more pull request comments than lines changed in the patch.

What is sometimes difficult to remember as a maintainer is that a pull request does not represent the start of time invested by a contributor. A pull request is usually the end of their time-investment. In this case I had already invested between 5-8 hours of profiling and understanding the issue before I could create the change.

Hidden in the yak-shaving was useful feedback but the process was so frustrating that I eventually threw in the towel and asked Nick to take it over after about 12 hours of total time invested.

Of the currently open pull requests the one with the most comments is at 99. Of the closed pull requests my maddening 84 comment odyssey doesn’t even fit on the first page of “most commented” pull requests. The top spot is claimed by this pull request which has 369 comments and took over two months from open to merge. That monster is somewhat of an outlier because it represents a substantial change earlier in the history of Delta kernel but a number of other changes are very much in hundreds of comments range.

The pull request culture in Delta kernel is fundamentally contributor hostile.

The suggestions I made to Nick on how to improve this are:

- Assigning one maintainer (e.g.

CODEOWNERS) to review each pull request. There is relatively little benefit from multiple people offering differing opinions on a non-maintainers’ pull request. - Contributors should feel like their goals are shared with maintainers. The suggest change functionality of GitHub pull requests is fantastic for this. Rather than leaving a wall of text, suggesting direct code changes helps convey a shared investment in the pull request.

- Better yet, rather than asking for tests or changes. Make the changes. Most contributors allow maintainers to push to their fork’s topic branches. I regularly use this to add regression tests to contributors’ pull requests, rather than asking them “please write a test.” Modelling good behavior usually is more successful than telling.

Some other ideas that come to mind:

- Any comment with “nit: “ should simply be deleted. I see this at work from time to time and will privately discuss with the developer how anti-social that behavior comes across. Any bit of feedback that somebody feels is nitpicky should be made in a follow up pull request or just not. Nitpicks are a waste of everybody’s time.

- There is a habit to “stack PRs” in this project and as I write this, there are 19 open “stacked” pull requests. Smaller commits and smaller pull requests should be preferred and move quicker. I think there are a lot of comments on pull requests because each pull request ends up being fairly large and sits in an Open state for a long time.

Many developers believe that code “stabilizes” as if some magic happens to code

in main. All code has a rapidly decaying half-life, especially code which

sits in open pull requests. The only way to demonstrate that anything is good

or bad is for it to be used. Stability comes from use.

I think everybody involved in the Delta kernel project, myself included, wants a stable and high-performance foundation to build our Delta-based applications. As Jez Humble and David Farley wrote in the book on Continuous Delivery, a long cycle time is usually antithetical to stability and reliability.

They’re good kernels Brent

Golly this has been a bunch of words. To quote a wise man:

The Delta Kernel is one of the most technically challenging and ambitious open source projects

I believe in the vision of Delta kernel and certainly wouldn’t be here if I didn’t. The fragmentation that I see in the ecosystem causing nothing but trouble. Since starting this essay I have encountered two new and quirky derivatives of delta-rs code which are trying to coerce it to do things which Delta kernel is meant to support. In fact, the status quo of Delta kernel supports the two use-cases I stumbled into!

Having a stable and high-performance foundation means that features and improvements added into kernel benefit everybody! How marvelous is that? The trick is getting everybody to use kernel!

Kernel’s success is important to the Delta Lake ecosystem and numerous others. For kernel to succeed however I believe we need to adjust course in 2026 to build a stronger technology foundation by introducing more idiomatic Rust code. Leaning more heavily on the strengths of the Rust ecosystem in the interfaces, supporting Rust implementations with async/await as a focus, rather than FFI.

Building in a more Rust-familiar way will enable more new contributors along with their fresh perspectives. We will need to improve our release cadence and change management into something clear and predictable. Making new developers feel welcomed and their contributions valued will solidify kernel’s place as the foundation in the ecosystem.

Stronger technology and a stronger community in 2026 will help Delta kernel overcome the challenges we face today.